Translation/Interpretation/Caption Text:

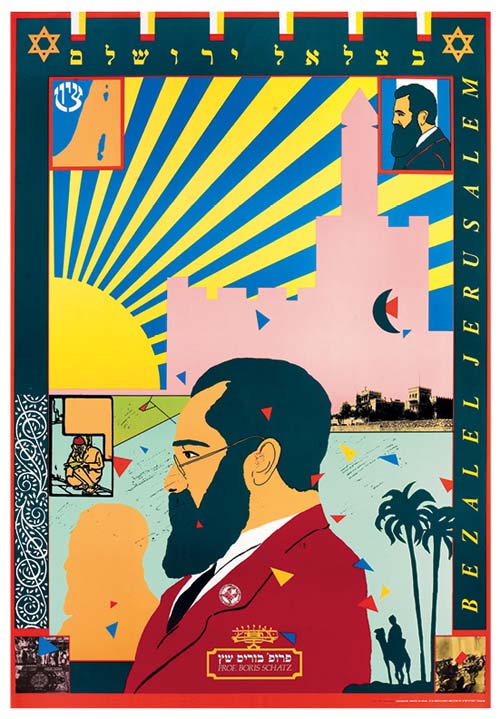

Boris Schatz was the founder of the Bezalel School (1906)

This poster was published by the artist, a graduate of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, as an homage on its 75th anniversary.

_________________________________________________

Analysis/Interpretation/Press:

Pure Blood, Tinder and Skype: The Utopia Envisioned a Century Ago by the Father of Israeli Art

Haaretz

By: Ofer Aderet

In 1918, Boris Schatz, founder of the Bezalel Academy of Art, conceived of the future Israel as a high-tech, peace-loving, vegetarian country where free love reigned supreme. But a eugenics program was also part of his vision

Dec 04, 2018 6:46 PM

According to the utopian vision of Boris Schatz, the founding father of two iconic Jerusalem institutions – the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design and the Israel Museum – the city would one day also host an additional prestige venue: a “Garden of Love,” an official site for forbidden liaisons between men and women. It is “one of the greatest moral institutions we have created here,” Schatz wrote, “a solution of genius to the grave and saddening difficulties that humanity could not solve formerly,” Schatz wrote in his 1918 novella, “Jerusalem Rebuilt: A Daydream,” about life in Palestine as he imagined it would be a century later.

Is it possible that early in the 20th century, long before the advent of the internet and the mobile phone, the father of Israeli art predicted Tinder-type dating? His idea bears more than a passing resemblance. In the Garden of Love, “one’s heart is not given to anyone. No one knows to whom he is giving his heart. Neither he nor she even knows the other’s name,” Schatz wrote in his vision. “The man and the woman meet there, do not get involved in a heartfelt relationship, but the one helps the other to get free of a natural need, to quiet the blood and the nerves, whose operation was amiss, because they could not fulfill natural law.”

Boris Schatz, a deft futurist. A 1982 poster by David Tartakover.

Schatz makes it clear that he is not referring to prostitution or other forms of sexual exploitation: “There is no place here for selling and buying people for mere pleasure, as occurred formerly. Both [participants] are free people. Both have come there to fulfill their natural need and they will help each other, out of the kindness of their heart, to achieve this.”

In one sense, the sexual encounters in the Garden of Love in Jerusalem are the most sublime realization of love. “Because those involved don’t know each other, and possibly will never meet again, their love becomes pure, abstract: love for its own sake, without any ulterior motives, side issues, accounts to settle or extraneous influences,” he wrote.

“Jerusalem Rebuilt” is “a very personal story, spawned by distress,” says the curator and art scholar Yigal Zalmona, a member of the Bezalel Academy faculty. Schatz, who was born in Lithuania in 1866, attended a yeshiva but left early to study sculpture and painting in Vilna, Warsaw and Paris. Subsequently, he established the Royal Academy of Art in Sofia, Bulgaria. In 1903, he met Theodor Herzl not long after Herzl published his utopian novel, “Altneuland” (The Old New Land), describing a visit to an imagined future Land of Israel. Their meeting converted Schatz to the Zionist cause.

Inspired by the book, in 1906 Schatz founded the Bezalel School of Art and a national museum, forerunner of the Israel Museum, in Jerusalem. However, his professional advancement was curtailed by World War I. Toward the end of the conflict, Bezalel was shut down by the Turks and its founder deported to Damascus. “There, in a cockroach-ridden prison, he started to write the book,” Zalmona says. Writing in Yiddish, he completed the work in Tiberias and Safed, where he remained in forced exile from Jerusalem.

However, Zalmona says, “Salvation was already on the horizon, because the British had arrived in the country.” Perhaps this was what allowed Schatz to transcend his personal difficulties and offer an elaborate and optimistic vision for the Land of Israel in 2018. Its hub was a modern, progressive, clean Jerusalem, very different from the city Schatz knew a century ago – but also not corresponding to today’s Jerusalem.

“It’s very easy to dismiss the book as nonsense, and the nostalgia and amusement it arouses are also understandable,” Zalmona observes. The book will be the focal point of a conference at the Israel Museum and at Bezalel on December 9-10, titled “Boris Schatz: From Sofia to Jerusalem and Beyond 1918-2018.” In Zalmona’s view, the fact that the conference is a joint event of the Israel Museum and the Bezalel Academy shows that his vision was fulfilled, not confined to utopian realms.

An optimistic vision for the Land of Israel. Illustration by Michal Boneno.

Still, Schatz’s vision transcended the world of art. In the novella (which is available online – in Hebrew translation – in a text version at the Project Ben Yehuda website and through the National Library site), the author falls asleep in 1918 and wakes up a hundred years later. He flies across the country’s skies accompanied by Bezalel Ben Uri, the chief artisan of the Tabernacle in the Book of Exodus, for whom the art academy is named.

Enlightening holidays

Between the lines, Schatz emerges as quite a deft futurist. For example, decades before homes in Israel had telephones, he predicted Skype-like conversation. “A beautiful woman with an infant in her arms… looked exactly like the cloth screen in the moving pictures,” he wrote about the display in the “telephone station,” one of many scattered around the city.

Light in the holy city would be supplied by solar energy. “On the high towers are bent mirrors that concentrate the sun’s rays. The vast force that accumulates there will be worked into electric light,” Schatz wrote. Electric power will reach every house. “The steel wires that are attached to every house made me realize that electric power did away with the steam engines here.”

Sophisticated public transportation would be diverse and free, with a genuine innovation: moving stairs. “Throughout we traveled from place to place by different means: by automobile, by moving sidewalk, by the cable route to the top of Mount Carmel, and from there we flew by airplane to Acre,” Schatz writes of his trip through the country. “We returned from Acre in an electric boat… There is no class system on the train – whoever arrives first gets a better seat. The carriages were extremely comfortable. The train moved, by means of electric power, at great speed and almost without any shaking. One could read a book at leisure, but I couldn’t pull myself away from the window.”

The buildings and factories in Schatz’s utopia have central air conditioning. “And in the summer, ice shall be placed there to cool the air, and the climate can be easily adjusted as needed,” he writes.

The economic organization of the utopia was socialist. For example, private property was abolished so strictly that people no longer invited guests to visit, because they had nothing to offer them. Social encounters were held in “popular meeting places, clubs and other public venues.” In former times, “guests would rob a person of his residence and his freedom, would spread the luxury, the ostentation, the unemployment, the slander, empty ceremonies and deception,” Schatz writes. At the same time, common dining rooms eliminate the need for home kitchens. In Schatz’s vision, food substitutes are developed in 2018 Israel. Thus, “people living in the next generation will not have to kill animals for food, will not have to work so hard to fill their stomachs and expend so much energy to maintain life.”

Food will be supplanted by laboratory-manufactured “essences,” to provide “every person with all he needs for his natural subsistence along with the enjoyment of tastiness and a pleasing aroma.” Alcoholic beverages (without alcohol) and cigarettes (without nicotine) will be sold only in drugstores. “Desist from poisoning the people in order to augment the government’s revenues,” he writes.

In Schatz’s utopia, every citizen is entitled to two months of vacation a year, in addition to Sabbaths and holidays. “On days off, the workers visit various exhibitions, take practical courses, attend lessons in the popular college, sit for examinations, participate in different congresses and in competitions of gymnastics societies. The vacation months bring no less benefit to the whole people than the working months.”

Much of Schatz’s account of utopia is devoted to social changes involving the gender balance of forces. Throughout, and on this theme, too, a complex, contradiction-ridden picture emerges. On the one hand, “Women are no longer domestic cooks for the family… The wife has ceased to be a woman of the cooking pot… and has been liberated from the kitchen and its brain-addling habits,” Schatz notes.

At the same time, women will be liberated from another burden as well: having to adorn themselves and dress up for men, and wear the latest fashion. “It is the way of the woman to beautify and decorate herself, seek to curry favor in the eyes of beholders, particularly if she is beautiful. Her nature has not changed even now, but her taste has improved, for the men have become more aesthetically-minded,” Schatz explains. “Now women have ceased to dress up in glittering objects… No longer will a woman look at a man in an effort to stir his passion, tickle his nerves.” For he would consider that to be unsavory, wild, unaesthetic. He seeks a woman’s natural beauty… Accordingly, the fashion seasons have now been cancelled.”

No place for the weak

In contrast to the men, who in this vision would do national service after their schooling, the women would be obliged to attend “Mother Israel,” an institution in which they would be taught how to be mothers. “A woman who is a good mother fulfills the most important duty for the benefit of the people,” Schatz avers. Still, not every woman is worthy to be a mother in Israel 2018. In this connection, a glaring disparity looms between the rosy future he depicts and the controversial ways he proposes to achieve it, some of which later graced Nazi and other benighted regimes.

“Now children will be born only to the elect, whose blood is absolutely pure and who have attained perfection of body and mind,” Schatz writes, describing a breeding program that recalls Nazi eugenics, which aimed to ensure that only the racially “fit” would reproduce. (The eugenics movement was also active in Europe and the U.S. in the early 20th century.)

“Not every person is duty-bound or wishes to create a new generation ‘in his form and image.’ That obligation devolves only on humanity’s elect, only those whom we would want all people to resemble,” Schatz writes. “In olden times, only the sick in body and mind refrained from endowing the world with children like them. This sexual abstinence was very useful in eradicating the diseases until they disappeared completely from the Earth. Afterward, weak, untalented and unseemly people also ceased to raise up seed.”

In Schatz’s vision, peace and harmony prevail in Israel, even between Jews and Arabs. “True peace between us and our neighbors… We have reconciled with the Bedouin, too,” Schatz writes. Following World War I, “the Peace Congress decided to eliminate and destroy all the world’s weapons.” Accordingly, “With the help of the Great Powers the arms of the Bedouin were taken from them… Because they could not obtain new arms, they stopped living by the sword.” Indeed, in this utopia the Jews teach the Arabs civility to the point where “many of them converted to Judaism even though we did not make an effort to Judaize them and to bring them under the wings of the Divine Presence. We taught them only the laws of honesty and justice.”

The major obstacle to peace has also been neutralized. The center of the country is the Third Temple, which Schatz envisions will be established by agreement between the Jews and the Arab minority, but will serve as a museum of art.

The form of government is “a social democratic republic” led by the Sanhedrin, headed by a president, a spiritual leader who is elected for life. However, Schatz’s portrayal indicates that this is not a democracy of a kind familiar to us today, but an oligarchy of intellectual elites.

Another institution in Schatz’s “daydream” is the “Valley of Ghosts,” which is “a place to die in.” It’s there that those who are about to die are sent. “Everyone who goes to the Valley of Ghosts is already considered dead in the eyes of all the living. He parts with his friends and relatives before going there.”

Schatz himself died in 1932 in the United States, while on a fundraising campaign for Bezalel. He was 66. He hadn’t manage to get his book published until 1924, six years after it was written. He was forced to scrap a plan to publish additional sections of the novella and had to abandon his hope of making money from the sales of “Jerusalem Rebuilt.” Today, a century later, original copies are sold at high prices in auctions and by antiquarians.

Source: